EVEN now, after all these days without electricity, can there be anyone out there who has at last memorised their MPRN number?

The MPRN, like all those numbers corporations give you, is supposed to be the number they remember you by. ESB asks for it every time you ring them, blue-fingered in the darkness. “Hang on,” you want to say, “this MPRN thing was your idea. If it’s such a handy way for you to identify me, why don’t you remember it?”

You don’t say that, of course. No one is mad at ESB because there’s been no power since Wednesday. Everyone knows they’re doing all they can. Honestly, you’d sooner sit in the dark for a week than demand that men be sent up poles in a hurricane. Still, though, it’s a niggle, the MPRN business; it’s something of a match in the powder barrel.

At any rate, ESB makes it clear almost immediately that it’s not interested in taking calls from people wanting to shoot the breeze about corporate identification – or even about when the power might come back. The recorded message on the ESB’s fault and emergency line says as much: “Are you actually in the throes of a heart attack, your legs trapped under a fallen electricity pole that’s also on fire? No? Thought not. Please hang up then,” or words to that effect.

Things get so old school in a power cut. If you’re lucky enough to have an open fire or a range, you’ve got one warm room in the whole house – just like the old days! Boiling Golden Wonders on an elderly Rayburn, you begin to wonder if there mightn’t be space on the walls for a picture of John F Kennedy and a Sacred Heart.

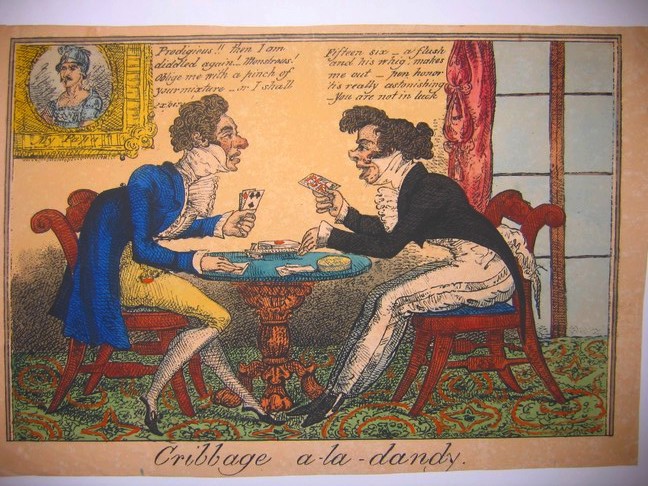

You play Cribbage by candlelight. Yes, Cribbage. Cluedo, it has emerged, is not an ideal game for two players: “I didn’t do it, so it must have been you”. And Monopoly is well known for causing even more damage to a relationship than three days spent alone together in post-apocalyptic conditions. Cribbage keeps things nice and courtly.

You forgot the advice – such good advice – always to charge your mobile phone before a power cut, but after three days (or more like three hours) everyone’s iPhone has died anyway. Mobile communications begin to seem like something we flirted with briefly – something we can now question the wisdom of, in hindsight.

The landline, improbably enough, stays working throughout the whole misadventure, which is lucky. Things are bad enough without having to deal with Eircom, and anyway they have something in their customer charter about not conducting repairs when there’s an R in the month.

There’s no light, no heat and ultimately – when the last drop from the inoperative pumping stations reaches you – no water. More importantly, there’s no radio, no television, and no internet. That means no access to the news. I repeat, three days without news. In the darkest hour of this, when you hit rock bottom, you have to admit you’re helpless, conduct a searching and fearless moral inventory, and turn yourself over to a higher power. There are nine other steps too which you must look up on the internet when the electricity comes back.

Two important notes to self after half a week of powerlessness: one, find out if they’re still making wind-up radios; two: write the MPRN number on the wall beside the phone.